What's Next for Crop Producers?

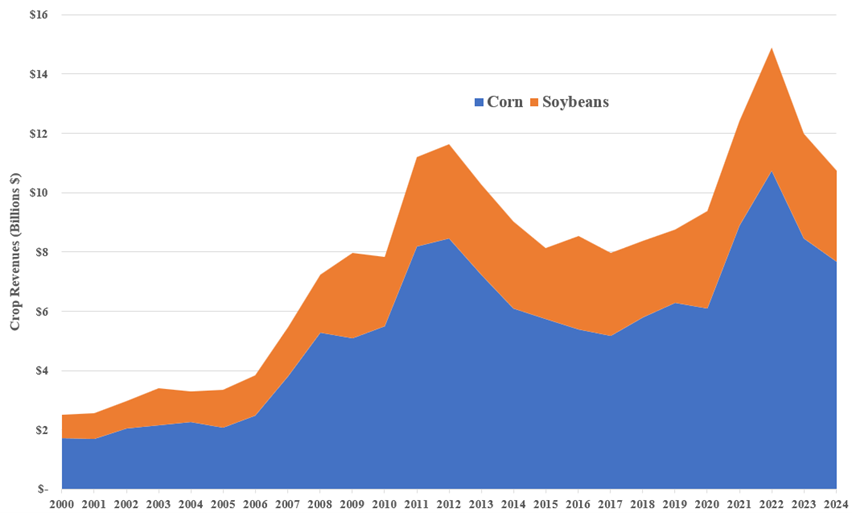

Nebraska crop producers have seen considerable growth in the demand for their commodities since the turn of the century. As a result, corn and soybean receipts in 2024, $10.7 billion, were 4.3 times those received in 2000. Receipts hit a record $14 billion in 2022, more than 5.5 times 2000's receipts (Figure 4). Soybeans and corn typically account for around 90% of the state’s crop receipts. Rising receipts led to record farm incomes. Nebraska net farm income hit new records six times over the past quarter century.

FIGURE 4. Nebraska Corn & Soybean Receipts

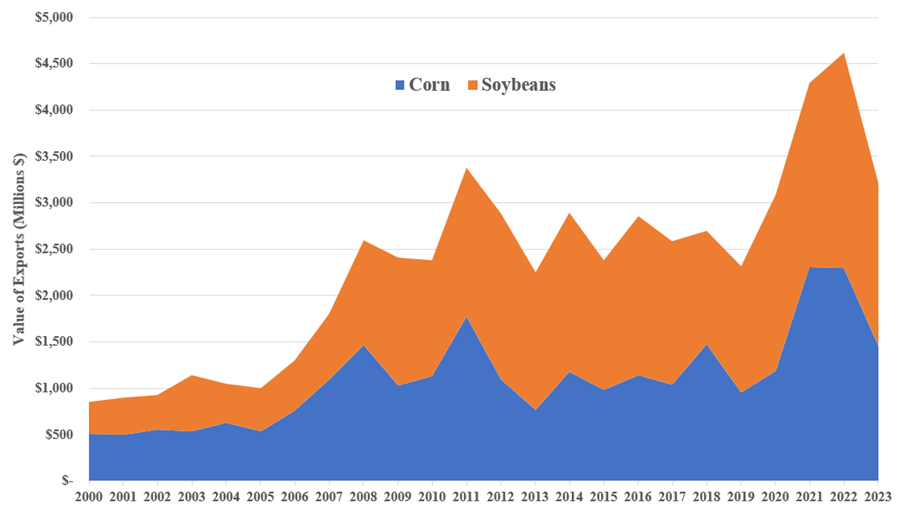

The primary influences in the growth of demand over the past 25 years were expanding ethanol production and thriving exports. Nebraska’s ethanol production in 2023 was a whopping 519% greater than production in 2000. The state’s ethanol production incentive program and the federal Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) played large roles in this expansion. Similarly, the value of Nebraska corn and soybean exported in 2023, $3.2 billion, was 276% greater than exports in 2000. And 2022’s exports were even greater at $4.6 billion (Figure 5). Multiple free trade agreements and China’s entry into the market opened doors for U.S. agricultural products. Nebraska commodities were the beneficiaries.

FIGURE 5. Value of Nebraska Corn & Soybean Exports

It’s difficult, though, to foresee ethanol and export-led growth continuing at the same pace. Consider trade. Institutions and agreements put in place to foster free trade are now ignored as countries become more nationalistic and turn inward, raising tariffs and implementing export controls. Managed trade, where import and export decisions are made at the whims of countries’ leaders and not by market conditions, are now in vogue. Trade now is viewed more as a means to gain leverage for geopolitical purposes, not so much as a means open the spigots to economic growth.

Additionally, U.S. crop producers face intense competition from growers in Brazil and Argentina and are losing their comparative advantage and market share in global markets. Land used for soybean and corn production in Brazil has expanded 40% in recent years with exports growing similarly. And Chinese investment in new railways and ports in South America means it’s less expensive for producers in these countries to transport their crops to market. The changing trade frontier could be especially problematic for U.S. soybean producers as typically 40-50% of the crop is exported. Corn exports generally make up around 20% of production.

The future for ethanol and biofuels as a continued source of growth looks uncertain too. Nebraska’s 24 ethanol plants have a combined capacity of 2.44 billion gallons; however, production has stagnated at just over 2 billion gallons in recent years. A change in federal policy allowing the year-round usage of 15% ethanol blended fuels, the potential usage of ethanol in the production of sustainable aviation fuel or maritime fuel and growing exports could boost demand. But the ongoing decline in gasoline consumption due to slower population growth, an aging population, more fuel-efficient vehicles, and the transition to electric and hybrid vehicles hang over the sector in the long-run. Soybean producers could see growth from the expanding usage of renewable diesel in the near term. The latest RFS quotas could mean an increase in crushed soybeans usage of more than 5 million metric tons according to the EPA if approved, although this amounts to just 4% of soybean production.

Ethanol, biofuels, and export markets aren’t going away overnight. However, the pace of growth which sustained corn and soybean production over the last 25 years is not likely to continue. The supply of U.S. corn and soybeans is projected to increase in coming years. New markets will need to be found to absorb the increased production. This is agriculture’s challenge for the next quarter century.